Integrated Community Care: bringing a new concept of care into messy real-world situations

In the midst of today’s energy crisis, citizens and care and well-being professionals have an acute sense that the old models of primary care are not robust enough to protect people in vulnerable situations. They are becoming convinced that Integrated Community Care, where care and support are organised alongside the individual and the local community, is a more sustainable concept. What is less certain is how to do this.

The annual conference of the European Forum for Primary Care (EFPC) was held from 25 to 27 September in Ghent. This forum brought together primary care organisations and professionals, researchers and policymakers from 33 countries. One of the workshops was organised by the Transnational Forum on Integrated Community Care. Transform is a joint initiative by foundations in Europe and Canada that places the local community, district or neighbourhood at the centre of integrated primary care.

During the first of two panel discussions in this workshop, the speakers indicated that care means much more than curing diseases or helping people to recover from them; it must help people to flourish. Integrated Community Care can help to put this new narrative of care and support into practice. That is because care means much more than simply caring for people. It also means caring about them and caring with them, and involves the whole of our society, both people and the planet itself. That is because it is much harder to be a caring household in a society that does not care”, said Dr. Andreas Chatzidakis from The Care Collective.

It is important for all those involved to understand how they are part of a collective that adapts its governance to meet the challenges that arise. “Dealing with a pandemic requires a different kind of collaboration from preparing a local community for long-term challenges, where you need a cluster approach to allow different ideas to come to the surface”, said Tobias Luthe, Founding Director of the Monviso Institute.

“We must ensure sure that these collectives are not co-opted by governments or businesses, because communities are quite weak institutional actors”, warned Chatzidakis. If that does happen, governments or businesses will take the initiative and there is a risk that the original community-oriented approach will be lost.

Geertrui Serneels, a psychologist and CEO of Solentra, issued a warning based on experience in practice that the ideal of ICC is not the reality. Solentra works with refugees, and not everyone feels that they are part of the community. “The community has its boundaries too, and it does not always put them in the right place.”

A demand for reference points

It is clear where we want to go, but how do we get there? This was the approach adopted by the second panel discussion, in which three speakers contributed front-line experience. “In real life, ICC is messy”, said Julie Zimmerman, Provincial Director of Primary Care and Virtual Care at the Foundry, which works in Canada to promote the mental well-being of young people and young adults through information and online services, and through integrated community centres.

She emphasised that ICC is a work in progress, with a move away from service provision or care delivery and towards co-production and co-creation of care and support. “Communities are ecosystems comprising many different organisms, and we are only one of these. It is our job to listen to the stakeholders – to young people and their networks first of all – to see what contributions we can make and the best ways for us to help the ecosystem flourish.”

This does not happen by itself. “Not everyone wants the same things. It takes a lot of difficult conversations, and both power and responsibility need to be shared. It is our role to act as a catalyst to help the community to define what service provision it wants and how we can contribute towards that. There is no single template.”

To make sure you do not lose sight of the goal, you need to start evaluating right at the start, from the first stage of a collaboration, says Amy Salmon from the Centre for Health Evaluation & Outcomes Sciences. “ICC is the result of colliding visions. The process of evaluation can help to bring partners together, formulate common goals and identify unwanted effects.”

In Flanders, ICC is also being supported by the Flemish Government. Nevertheless, Caroline Verlinde from VIVEL says this does not lead to a rigid top-down approach. “Primary care zones are defined by communities themselves. There is a framework, but it is flexible. The structure is the same everywhere and the participating organisations are the same, but based on an analysis of the needs of the local population, they can do very different things.”

Read the interview with Maria van den Muijsenbergh, Chair of EFPC, under the logos

Primary care must not be doomed to just firefighting

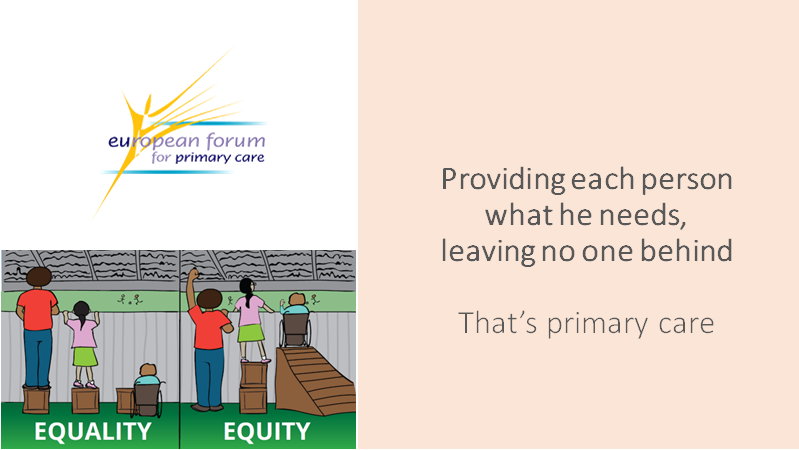

Integrated community care is needed more than ever, says Maria van den Muijsenbergh, Chair of EFPC. “We know that the people who have the most health-related problems often have the least access to care and support. We also know that physical symptoms do not always have physical causes, and that conditions in society and social determinants play a part as well.”

Integrated community care is needed more than ever, says Maria van den Muijsenbergh, Chair of EFPC. “We know that the people who have the most health-related problems often have the least access to care and support. We also know that physical symptoms do not always have physical causes, and that conditions in society and social determinants play a part as well.”

Right now, there are a lot of social and economic problems that are causing people chronic stress. Van den Muijsenbergh says that this is precisely why it is important for doctors and nurses to work together, not only with other professionals in the care sector but for example also with social workers, and to look not just at the individual but at the context in which they live as well. “Which neighbourhood is it? Who lives there? What environmental factors are there? What causes stress? What do they need? What makes people sick? What is really important for patients?”

“Listening is essential. The voice of the person or patient must be much more clearly heard. We need to work on this in a structured way, since the status quo is still too supply driven.” Van den Muijsenbergh thinks that care and well-being professionals need to have the courage to think about changes in the way they work to respond to a changing society and address the questions that people are asking as a result of those changes.

A robust, well-integrated primary sector can also reduce the number of more expensive treatments required by taking action at an earlier stage and in a more preventive way. By asking what people really need, finding out what is behind physical symptoms, a doctor can see what other services could do and what the individual and the community can take on themselves, which will also reduce the pressure on scarce health care staff.

Van den Muijsenbergh warns, however, that this does not take away the government’s responsibility to improve the macro-environment and take structural measures to promote a healthy environment, pleasant public spaces, safe roads, efficient help with financial problems and adequate numbers of health care staff.

“The government must consolidate the work of primary care. If there is a staff shortage, the GP needs to ‘get through’ patients as quickly as possible because he has so many of them to see that day, and he cannot ask the really probing questions. If the dimension of a supportive government is lost, primary care ends up just firefighting.”

At the same time, it is important not to idealise the community that shares this responsibility. “Not everyone really wants to get involved. In each neighbourhood you have to look at who is able and willing to do this and what form it can take. ICC as defined by Transform is a new care concept. It offers guidance, together with effectiveness principles, that make it possible to progress gradually. “You don’t have to go all the way immediately. In reality, situations can be a lot more difficult. People find it hard to let go of established positions, and primary care is operating under a lot of pressure. Nevertheless, care and assistance providers do feel a sense of urgency, and they are aware of the need for practical reference points. If primary care professionals and organisations work together more, really consider each person’s needs and gradually assemble a network in a neighbourhood to meet those needs, we will be moving in the right direction.”

Make sure to visit the TransForm and EFPC website and to check out this video interview with Maria van den Muijsenbergh